As we turn the page on the calendar and embark on a new year, the outlook for the investment markets seems abundantly clear. The economic expansion, while on shaky ground at various points in time last year, now appears to be solidly on track. Growth is stabilizing, and we’re seeing a firming in the previously weak manufacturing sector. Fears of recession have dissipated. Virtually everyone is bullish on U.S. stocks. However, no one expects a repeat performance of last year’s whopping 31.5% gain in the S&P 500. 2019 was, by many accounts, a once-in-a-decade performance. Most analysts expect the stock market to return somewhere in the low single digits. There are few bears – or uber bulls – on Wall Street.

With the announcement of a phase one trade deal between the U.S. and China, many market strategists think this could be the year that international and emerging markets stocks finally break out, catching up to U.S. stocks after lagging behind for many years. With the Fed likely to hold interest rates steady for the time being, most analysts think the bond market will merely eke out a return in line with its coupon rate, nothing like the 8.7% return it posted last year. Everyone seems to agree that the double-digit returns of balanced portfolios in 2019 will be very unlikely to repeat. The outlook for 2020 is clear: good, but not great.

Our investment team has reviewed summaries of the forecasts of over 500 of the world’s financial institutions, and, although their opinions vary in some measure, for the most part they paint a remarkably consistent picture of the future. Consider the following few excerpts.

Barclays

“We believe that there is a strong case to expect positive, if modest, returns in major asset classes.”

BlackRock Investment Institute

“Growth should edge higher in 2020, limiting recession risks. This is a favorable backdrop for risk assets.”

Goldman Sachs

“We expect moderately better economic and earnings growth, and therefore decent risky asset returns.”

HSBC

“Our baseline scenario for 2020 is relatively favorable. We anticipate slow and steady growth, low inflation, accommodative policy and single digit profit growth.”

Robeco

“We expect the economic expansion to last a little longer, and the equity bull market to enter the last leg of a near decade-long climb.”

State Street Global Advisors

“We believe that the global economic recovery will continue in 2020, although it may have to sidestep substantial risks to sustain momentum.”

This is just a small sampling of the predictions we reviewed, but they provide a sense of the consistently favorable narrative among Wall Street firms: continued economic expansion, a reduced risk of recession, slow growth, low inflation, interest rates in check, and positive though modest returns.

When we independently assess the outlook for 2020, looking carefully at the economic data and reviewing each asset class in rigorous detail, we arrive at essentially the same view. Our base-case scenario matches the consensus.

The illusion of safety

In a field where the outlook is notoriously hazy, are the consistency and clarity across Wall Street to be celebrated? Are they a sign of greater-than-usual confidence in the future? Not necessarily. As comforting as it is to have consistency and clarity, it’s actually a bit worrisome. There’s a sense of safety in numbers, but that sense of safety is often an illusion. The problem here is that while the consensus is sometimes right, it’s often wrong. In fact, it’s wrong more often than not.

To give but the most recent example of when the consensus was wrong, let’s rewind the clock to a little over a year ago – the fourth quarter of 2018 – and consider what the economic and market environments looked like at that time. After a decade of unprecedented monetary easing in the wake of the financial crisis, the Fed finally began to embark on a process of “normalization” by raising interest rates and reducing its bloated balance sheet. Unfortunately, this proved to be a case of very bad timing. No sooner did the Fed begin raising interest rates than the global economy suddenly began to slow.

In the U.S., the boost in growth from the tax cuts was beginning to moderate. China’s growth was slowing. Europe, faced with the uncertainty over Brexit, was slowing. There were signs of cracks in the global economic expansion. The U.S.-China trade war, which most people thought would eventually get resolved with some sort of agreement, suddenly became protracted. With heightened rhetoric on both sides, and especially President Trump’s surprise tweet announcing additional tariffs on top of previously announced tariffs, the trade war suddenly seemed to have no end in sight. Global trade, business investment, and manufacturing all began to slow.

Frozen II

Faced with the uncertainty of tariffs and the prospects of a protracted trade war, business leaders were suddenly frozen. And who could blame them? Recession risks rose sharply from around 10% to as much as 50%. We reached a level of drama to match the plot of the blockbuster Disney film launched that quarter, “Frozen II,” but without the predictably happy ending. The Rotten Tomatoes review of the movie referred to it as “a dramatic adventure into the unknown,” which seems an apt description of the economy and the markets at the time. Investors were enveloped by a wall of mist as thick as that which trapped Elsa, Anna, Olaf, Kristoff, and Sven in the Enchanted Forest. The S&P 500 collapsed, declining 19.8% from peak to trough in the span of one quarter. Every major asset class ended up with a negative return for 2018, something that hadn’t happened in the past 15 years, even in 2008.

Suddenly, the mist cleared

And now, here we are, merely a little more than a year later, and we’ve witnessed a remarkable turnaround, a truly stunning reversal if there ever was one. It’s as if the mist that had enveloped the Enchanted Forest and similarly clouded investors’ minds had suddenly cleared. The S&P 500 gained 31.5% in 2019. Real estate, as measured by the NAREIT Index, jumped 28.7% for the year. And despite the trade war and slowing global growth, even international developed stocks posted a respectable return of 22.7%. Emerging market stocks, the worst-performing asset class in 2018, rebounded sharply too, with a gain of 18.3%. High-yield bonds produced an impressive return of 12.6%, while the overall bond market rose 8.7%. Faced with the depressing state of affairs at Christmastime, who would have predicted we would have had such an amazing 2019? The consensus was wrong.

The Fed pivot

What caused such a stunning turnaround? Several factors contributed to the rebound, but probably the single biggest factor was the “Fed pivot.” Sensing that the trade war was beginning to impact global growth and that things could definitely get worse, the Fed virtually turned on a dime and went from raising rates to suddenly lowering rates. It’s not clear how much of a direct impact the decline in rates has had on the real economy, but it certainly seems to have had an effect on business confidence, market sentiment, and financial asset prices. Bonds appreciated as interest rates declined. Credit spreads narrowed as recession risks receded, driving up the price of high yield bonds. With a lower discount rate factored into the valuation of stocks, the price-earnings ratio of the market expanded, driving the strong gains for the year. In short, virtually all assets were revalued upward.

Finally! A trade deal

The shift from what looked like an escalating and never-ending trade war to the sudden announcement by Trump of a phase one trade agreement further boosted market sentiment. The trade issue had weighed on the market at various points during the year, and thus the agreement, however modest it may be, was welcomed as progress. Investors breathed a collective sigh of relief.

Boris and Brexit prevail

The resounding success of the Conservative Party in the U.K. elections, with the party gaining a majority of seats in Parliament and securing Boris Johnson as prime minister, nearly guaranteed that the U.K will leave the European Union in January. This brought further clarity for investors and boosted financial market sentiment.

Unfrozen

As rates declined, a pending trade agreement was announced, and we finally had clarity on the Brexit process, business confidence began to improve. Corporate executives were no longer frozen. And the key piece of economic data that had caused such concern in 2018, the slowdown in manufacturing activity, began to improve along with it. Suddenly the narrative changed from the increasing possibility of a recession now to stabilization and improvement. And thus asset prices reflected this improvement. The mist had cleared. Market sentiment suddenly shifted to “risk on.” And here we stand today, with a consistent and clear story across Wall Street – everything is fine. The expansion should continue. Growth will be solid, even if slow. Expect positive though modest returns. Good, but not great.

Parts unknown

All of this sounds very logical. It reflects what we know today about the trends in the economy and the markets. But for our part, while this story makes sense and it’s consistent with our base-case scenario, we’re challenging ourselves to go deeper and ask some uncomfortable questions. What if the consensus is wrong? Just as the outlook in late 2018 proved to be far off the mark from what actually transpired in 2019, what could occur in 2020 to make the current consensus turn out to be wrong? What are the risks and challenges that aren’t being sufficiently appreciated?

We would humbly suggest that despite the comfortable consistency and clarity of the Wall Street story, we’re actually in “territory incognita.” Just like in the Enchanted Forest, a wall of mist is forming. We’re in the longest economic expansion in history. We’re coming off a year when the financial markets just experienced a once-in-a-decade performance. Assets aren’t particularly cheap. There are numerous risks out there that could derail the rosy consensus, and investors would do well to consider them more carefully.

By the middle of the 16th century, maps of North America created by Italian explorers showed that large sections of the continent had already been explored and thus were well (even if inaccurately) represented. However, there still were areas of the continent that remained unexplored and thus weren’t well represented on the maps at all. These areas were simply labeled “Terra Incognita” (unknown territory). In English parlance, we might say “parts unknown.” Some cartographers even labeled these unknown regions the “Land of Dragons” or “Land of Lions,” not because they believed that dragons or lions actually existed there necessarily (after all, how could they know?) but rather simply to highlight the potential risks and threats that might exist in these unknown regions. What are some of those risks for the investment markets?

On the brink of war?

Just as Wall Street was issuing its consensus story about a relatively rosy 2020 – and the market gains continued in the first few days of the new year – we suddenly experienced a bout of volatility, seemingly out of nowhere, as investors digested the fallout from the killing of Iran’s top military commander, General Qasem Soleimani, by a U.S. airstrike in Baghdad. Iran immediately vowed revenge against the U.S. Tensions suddenly rose dramatically and some observers thought we could be on the brink of possible war with Iran. Stocks dropped, oil prices rose, and money flowed into safe-haven assets such as U.S. Treasury bonds, gold, and the Japanese yen. Talk about a sudden change of events. We had entered the Land of Dragons and Lions.

Iran retaliated by launching a rocket attack on two U.S. bases in Iraq. Fortunately, there was no loss of life from the attack. Tensions cooled considerably when President Trump decided not to retaliate back, instituting additional sanctions against the regime instead. Investors breathed a sigh relief and markets steadied. It appears that the worst-case scenario of outright war has been avoided, at least for now. But, many observers believe the situation could escalate again. They point to the possibility of Iran continuing to engage in various forms of asymmetric warfare, further attacks in Iraq either directly or indirectly using proxy militias, attacks against U.S. allies in the region, including Israel, Dubai and the UAE, attacks on U.S. assets, cyberattacks, and resurrecting its nuclear program.

While the situation may escalate again, several market observers have pointed out that there have been tensions in the Middle East, including wars, for decades, and yet the financial markets have continued their upward march over time despite that. The U.S. military has been bogged down in Iraq for 17 years, since the invasion in 2003. But while it’s true that the financial markets tend to eventually move beyond geopolitical issues, escalating tensions between the U.S. and Iran, and certainly an outright war, would seem likely to result in some volatility for the markets.

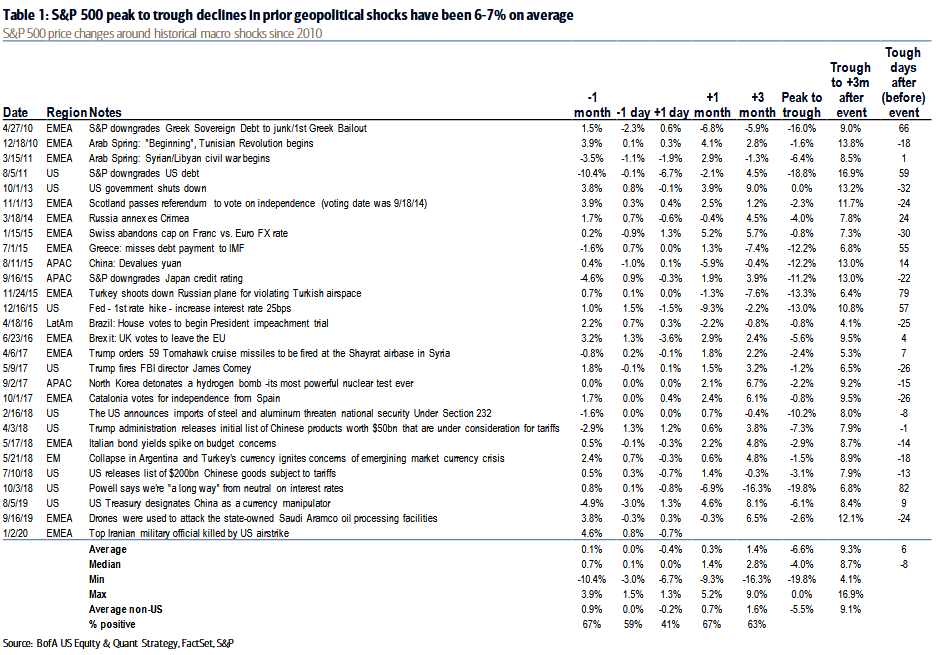

Table 1 shows the historical impact of geopolitical shocks on the stock market since 2010. The average peak-to-trough decline for the S&P 500 was 6.6%. That’s a fairly modest decline. However, the largest decline was as much as 19% – approaching bear market territory. The type of geopolitical shock matters, and one would think that an outright war with a formidable military opponent – especially one that historically has been developing nuclear weapons, such as Iran – could result in some serious downside. So far, the reaction of the markets has been muted, especially as tensions have cooled. But we’re mindful that all this could change in a heartbeat if tensions were to escalate again.

What else could change the story?

What else could cause a departure from the current consensus? With all the news coverage, campaign ads, and six Democratic debates so far, no one needs reminding that we’re in an election year and we’re about to enter the heart of the election season. And elections mean uncertainty for the market.

The central issue for investors, first and foremost, is whether Trump will be reelected. While there are clearly polarizing views about Trump (this is not about politics), he is considered by investors to be business-friendly, especially given his implementation of tax cuts and his administration’s emphasis on deregulation (although this view has been tempered at times by his stance on tariffs and trade, certain foreign policy initiatives, and his unpredictable nature in general).

If the online betting sites are any indication, Trump has no legitimate challengers. The odds say he is likely to be reelected. And when the House voted to impeach Trump, his odds actually improved, as the process seems to have energized his base. But the recent tensions with Iran, especially if they were to worsen substantially, could change the picture dramatically. And while the economy appears to be on solid footing right now, if that changes, Trump’s prospects could change along with it. Finally, keep in mind that the past two elections (Obama and Trump) were won by candidates considered long shots.

The other key issue for investors is who eventually will prevail as the Democratic presidential nominee. Will it be a more liberal/progressive candidate such as Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, or a more centrist/moderate candidate such as Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg, Michael Bloomberg, or Amy Klobuchar? The key concern is that if a liberal/progressive candidate were to become the nominee and ultimately prevail in the general election, there is a possibility of a reversal of the tax cuts (and higher taxes in general); a possible wealth tax; greater regulation; the promotion of Medicare for All characterized by a single-payer, universal health care system; and a generally less favorable business environment. As of this writing, according to RealClearPolitics.org, Biden is leading the pack with 31% in the polls, an eight-point lead over Sanders at 23%, followed by Warren at 14%. Warren gained momentum in the summer, emerging as a meaningful threat to Biden, but she has since fallen back in the polls. Buttigieg and Bloomberg are at 8% and 7%, respectively.

A less business-friendly administration, and especially a reversal of the tax cuts in particular (with corporate taxes going from 21% back to 35%), would likely have an impact on stock market earnings and hence valuations, causing some potentially significant downside. Suffice it to say we are watching this election season very carefully.

The trade war hasn’t gone away

We are mindful that just because phase one of a trade agreement has been announced, that doesn’t mean the end of the trade war. It’s progress, for sure, but we’re not entirely out of the woods. We’re still in terra incognita. The agreement does address some important issues, but it’s not a final deal. It involves the cancellation and reduction of tariffs on some though not all goods, in return for Chinese purchases of U.S. agricultural, energy, and manufactured goods (e.g., cell phones, laptop computers, toys, and clothing). It’s encouraging that the agreement goes beyond merely trade issues to address U.S. complaints about intellectual property rights, including stronger legal protections for patents, trademarks, and copyrights as well as criminal and civil penalties for pirated and counterfeit goods. The Chinese have also agreed to eliminate pressure on U.S. companies regarding technology transfer. Finally, in a somewhat surprising and positive development, the agreement also stipulates that the Chinese will refrain from competitive currency devaluations and exchange rate targeting.

While an encouraging step in the right direction, this is not a final agreement. There are many more issues yet to be resolved over time. And it remains to be seen whether the parties will live up to the agreement. Are the enforcement mechanisms sufficient? We have the sense that we need to prepare ourselves for ongoing trade skirmishes and battles over time.

All clear! Not so fast …

By outlining the risks that exist, we don’t mean to be overly pessimistic. As we said at the outset, our base-case scenario is that the economy is still in good shape and the backdrop for financial assets is favorable. But unlike many market mavens who signaled the “all clear” late last year and recommended a full risk-on stance, we’re somewhat more cautious. We remain positive, but we’re continuing to challenge ourselves to consider scenarios that are alternatives to the consensus. And far from adopting a full risk-on stance, we have maintained our position of playing offense and defense simultaneously as we await greater clarity on the outlook, especially as it relates to some of these risks. In terms of offense, we are maintaining our overweight stance to equities relative to bonds. With the economic expansion likely to continue, even if at a modest pace, and valuations only slightly above average levels, we think the stock market can continue to make gains. Those gains likely will be driven by earnings growth rather than multiple expansion, which means returns will likely be in the single digits.

This could be the breakout year for international

We continue to maintain some exposure to international and emerging market stocks. Over the past decade, U.S. stocks have been the best performer, trouncing international and emerging market stocks by a wide margin. That can’t continue forever. At some point, international and emerging markets will catch up. As investors continue to realize that the global expansion is solid and broadening again and that U.S. stocks are much more expensive than international and emerging market stocks, we think international and emerging markets could perform better than U.S. stocks in 2020.

In terms of defense, we continue to hold some cash and own U.S. Treasury notes and bills. We are maintaining our cautious stance on credit-oriented (e.g., high-yield) bonds and long-duration bonds (for which we feel you’re not getting sufficiently compensated at today’s yields). We are also maintaining some exposure to nontraditional, alternative investments that have a relatively low correlation to traditional stocks and bonds, thereby providing some diversification and risk-reduction benefits (e.g., select real estate, balanced funds, infrastructure, master limited partnerships, merger arbitrage, etc.). Finally, we have some modest hedged exposure with a position in gold.

Mapping the territory

While the outlook for the economy and the financial markets seems clear, as evidenced by the remarkably consistent predictions put forth by Wall Street, we remain mindful that the consensus isn’t always right. We remain optimistic about 2020, expecting positive though modest returns. However, we are watching the various risks carefully. We liken this process to the 16th-century Italian explorers who kept forging ahead, exploring the terra incognita, and watching out for dragons and lions. Once they eventually familiarized themselves with these new regions, their cartographers were able to more confidently fill out their maps. May the mist clear, the dragons and lions prove to be mythological, and we end 2020 on a new high!

As always, if you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out to your wealth advisor.