As if caught in a sudden snowstorm, investors were surprised by the near bear market in 2018 – an unusual occurrence without a recession. Not only were stocks down sharply, but nearly every asset class declined during the year as well, making it a challenging year, even for diversified investors. Winter unexpectedly arrived early. Investors remain uncertain about what’s in store for 2019. Will a nascent recovery in the first few weeks of the year continue, or are we headed for more troubling times? Are we in for a long, harsh winter, or is the season about to change?

2019 has finally arrived. And that means the most highly anticipated event of the past two years is close at hand – the airing of the final episodes of Game of Thrones, starting in April. Fans are eager to see how the epic series will conclude. We have little to go on for clues about this final season, except for a few teaser trailers that have been released and the November cover of Entertainment Weekly, which shows Daenerys Targaryen and Jon Snow against a wintery backdrop. This is a clue that Daenerys and Jon have arrived in Winterfell, in the north, known for its harsh winters. “Winter is coming” is the oft-repeated motto of House Stark. The phrase has become such a well-known cultural meme that even President Trump recently propagated it by creating a poster with his image on it and the tagline, “The Wall Is Coming.” The motto has a layered meaning. First, it means, literally, that winter is coming. But it also refers to the need for constant vigilance. Since the seasons can change unexpectedly, and winter in Winterfell is particularly harsh and can last for long periods of time, one must always be prepared. And according to George R.R. Martin, the creator of the book series on which the show is based, metaphorically it expresses the idea, more generally, that dark periods occur in life. Nobody is ever safe and comfortable for too long, which in some sense is one of the underlying messages of the entire Game of Thrones series. This seems to be an apt metaphor for investors, too. Winter unexpectedly arrived early, in the fall of 2018, in the form of a bear market – or rather a near bear market.

Like the seasons on the fictional continent of Westeros and the political fortunes and misfortunes of the characters in Game of Thrones, the year overall for investors was characterized by constant change and unpredictability. The U.S. stock market rose in the beginning of the year. It peaked and then declined in late January. It bottomed in February and then recovered fully, going on to post new highs by the fall. It peaked again in October and then went into a tailspin – nearly, but not quite, entering bear market territory with a decline of 19.8%. Winter had definitely arrived! The market bottomed on Christmas Eve and has risen 9% since. The hoped-for Santa Claus rally never materialized in 2018. Instead, investors got a lump of coal in their stockings. However, they did get a post-Christmas new year rally, which must feel pretty good. But looking back on 2018, what a roller-coaster ride it was. And even though the market has rebounded somewhat from the bottom, investors are left with the uneasy feeling that winter may not yet be over.

If it looks like a duck…

In our previous commentary, “Naked and Afraid,” we cautioned investors that “the U.S. market may continue to experience volatility, even a sharp pullback or correction.” Our predictions aren’t always right, of course, but we got that part right. We went on to say, “We are expecting neither a recession on the one hand nor accelerating growth leading to runaway inflation and aggressively rising interest rates on the other.” We got that right, too. We’ve been telling investors for some time that although we could see a correction (defined as a decline of 10%), a bear market (a 20%+ decline) was unlikely. Our record on that prediction, however, is a little ambiguous. On the one hand, our call was technically correct. The S&P 500 suffered a peak-to-trough decline of 19.8%, just barely avoiding, by a hair’s breadth, the technical definition of a bear market. So on the one hand, you could say that we got that right, too. But let’s not fool ourselves. While the S&P 500 may have technically avoided a bear market, it came so close that for all practical purposes we can call it a bear market. It certainly felt like a bear market. Six of the 11 sectors in the S&P 500 experienced declines of 20% or more. The Russell 2000 (an index of small-cap stocks) and the NASDAQ Composite both declined by over 20%. Emerging market stocks entered a bear market earlier in the year. You know the saying, “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck….” We’ll concede that we had a bear market. We got that one wrong. Winter is here!

The anatomy of a bear

Why did we think we would avoid a bear market? Because bear markets are almost always associated with recessions, and based on our view of the economic data and trends, we didn’t see a recession in sight – at least in the near term.

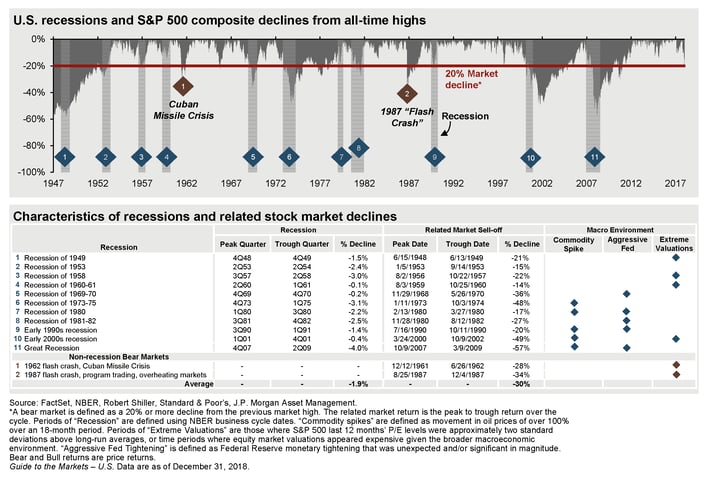

Figure 1. Recessions and bear markets

As illustrated in Figure 1, there have been 11 recessions since 1949. Eight of those 11 recessions were associated with bear markets. The other three recessions were associated with market declines, but like 2018, they failed to meet the 20% threshold definition of a bear market. Nevertheless, the market was down considerably during those three periods, anywhere from 14%-17%. There have been only two nonrecession bear markets in the post-World War II period – in 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis (when the market declined 28%), and in 1987, during the program trading-induced flash crash (when the market declined 34%). Other than that, we haven’t had a nonrecession bear market – until now – which is what makes 2018 so unusual. We came close in 2011. The market was down 19% that year, over fears of contagion from the European debt crisis and the credit rating downgrade of U.S. Treasury debt. But the market managed to recover and end flat for the year. We had a recession scare in 2015-16, prompted by concerns over an economic slowdown in China and a devaluation of the yuan (which triggered a 43% drop in the Shanghai index), plummeting oil prices (which declined from over $100 per barrel to below $27 per barrel), the Greek debt default, the end of quantitative easing and a corresponding sharp rise in bond yields in the U.S., and the U.K.’s Brexit referendum. The stock market declined 12% in 2015 before recovering to end the year down only 1%. It dropped 11% again in 2016 but recovered to end the year up 10%. Despite all those global macro events that triggered a fear of recession, the U.S. economy managed to avoid a recession in 2015-16 after all and the market eventually recovered.

Déjà vu all over again

We think 2018-19 will be a lot like 2011 and 2015-16. That is, there are plenty of legitimate global macro issues to worry about, but ultimately, we think the economy is strong enough to avoid a recession. And thus, while we can’t say we’ll avoid a bear market as a result of avoiding a recession any longer, since we just had a bear market – and since we still expect to avoid a recession – we think the market will recover.

A growth slowdown, not a contraction – a calculus refresher

The principal issue that caused the stock market decline in 2018 is a slowdown in economic growth globally. We think this is merely a slowdown, not a contraction. The economy is still growing, it’s just growing at a slower rate than in the past. For those of you who took calculus, you’ll recognize this as the second derivative. The first derivative measures the rate of change. The second derivative measures how much the change is changing. Said differently, the first derivative measures speed and the second derivative measures acceleration (or deceleration). In the U.S., we experienced an acceleration in GDP growth in the second quarter of 2018, to 4.2%, but that proved to be short-lived. It was promptly followed by a deceleration in GDP growth, to 3.4% in the third quarter. Economists expect a further slowdown, to 2.8%, in the fourth quarter. Much of the rest of the world is experiencing a deceleration in growth, too, including Europe and China. The global economy is like a driver who is still pressing down on the gas pedal but just a bit less hard.

So, why did we have a bear market when we were merely experiencing a growth slowdown and not a recession? The obvious answer is that investors were looking ahead – as they always do – and assumed that things would get worse. They assumed that the second derivative would continue to deteriorate, apparently inexorably, to the point where growth would eventually contract. A negative second derivative was an indication that the first derivative was about to eventually go negative too. And a negative first derivative of GDP is bad. That’s called a recession.

Investors were looking at the trend in growth and extrapolating it. Several factors seem to justify this extrapolation. Part of the slowdown can be attributed to the fading impact of the tax cuts. But what caused investors to really worry that the slowdown would turn into a recession were two key issues: an overly aggressive Fed, which appeared to be on autopilot, raising rates in the face of evidence of the slowdown, and the U.S.-China trade war, which has lasted longer than expected, with seemingly little likelihood of a resolution and which appeared to already be taking a toll on corporate earnings growth. As we approached year’s end, the mood darkened considerably. Bad news seemed to keep piling up, with plummeting oil prices, chaos in Washington, the impasse over the government shutdown, and, finally, Apple issuing a revenue warning, citing slowing iPhone sales in China (a second derivative event). The release of more second derivative economic data points, such as the ISM Manufacturing Index, which came in below expectations (but which still showed growth, not contraction), added to investor worries. The negative spiral continued – winter had arrived in full force – until Christmas Eve, when the market finally bottomed.

How did diversified investors fare?

The phrase “Winter is coming” is not just a forecast but also a reminder of the need to be prepared. The best way for investors to prepare for winter is by owning a diversified portfolio. That’s the first line of defense against a harsh winter, including a bear market in stocks. The theory, of course, is that by diversifying by asset class, if one asset class, like stocks, does poorly, then other asset classes, like bonds, typically do better, helping offset the poor-performing asset class and thereby cushioning the impact on the overall portfolio in the process.

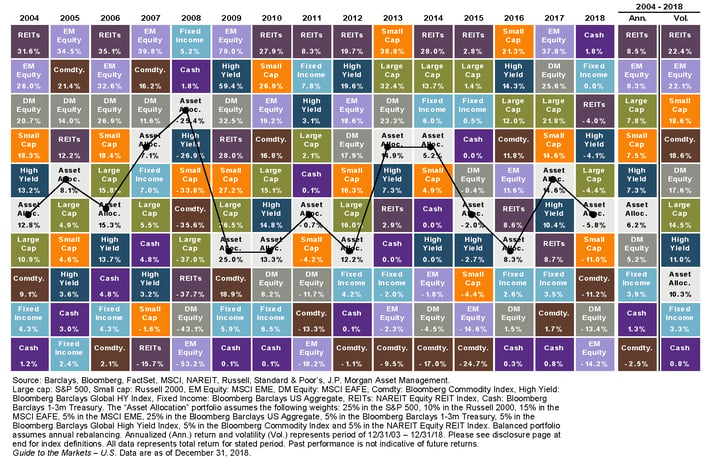

Figure 2. Asset class returns

As you can see from Figure 2, 2018 was an unusual year. It was a harsh winter in the sense that the only asset class that was positive was cash. Investment-grade bonds were flat. All the rest of the asset classes, including large-cap stocks, small- and mid-cap stocks, international stocks, emerging market stocks, real estate, high-yield bonds, and commodities, declined. As a result, a diversified benchmark composed of a mix of different asset classes, illustrated by the black line (and the white boxes), ended down for the year; in this particular case, about 6%. This was an unusual year, when diversified portfolios did worse than the U.S. stock market did during a stock market decline. This can be attributed to the fact that virtually everything else was down too, except for cash and bonds – and the flat performance of bonds wasn’t enough to help offset the decline in all the other asset classes. The fact that 2018 was an unusual year, and that diversified portfolios didn’t fare particularly well, isn’t a reason to abandon a diversified portfolio. As Figure 2 shows, diversified portfolios can go down occasionally, but they’re never at the bottom of the chart. And they do well, on average, over time. We would remind our clients to stay the course. Diversification is still the best way to prepare for winter.

Light at the end of the tunnel

The market bottomed on Christmas Eve and suddenly turned around, almost on a dime. What changed? It suddenly became clear – to use the language of calculus again – that the second derivative wasn’t leading inexorably to a negative first derivative. A recession was less likely. A harsh, long winter just might be avoided.

Three things happened. First, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell signaled that the Fed would be “patient” (a term he used four times in a recent speech) and that it would “watch and wait.” This suggested that the Fed was no longer on autopilot and that a pause in rate hikes was likely. Investors suddenly breathed a collective sigh of relief. The expected Fed rate hikes were now off the table. Second, trade representatives for the U.S. and China resumed trade negotiations. This was a sign of progress, albeit modest progress, but a positive sign nonetheless. Even if a trade deal was not imminent, the fact that the two sides were at least sitting down at the bargaining table was a good sign. News that China was unexpectedly sending Vice Chairman Liu He – the top economic adviser to President Xi Jinping – to the talks was a further positive sign. The Chinese seemed to be taking the talks seriously. And finally, a favorable jobs report, which showed that the U.S. added 344,000 jobs in December, well ahead of the 177,000 jobs expected – a decidedly positive second derivative event – indicated to investors that the economy may not actually be slowing as much as they thought. Suddenly, a negative second derivative leading to a negative first derivative – otherwise known as a recession – was no longer a foregone conclusion.

Our base case

Although we’ve spent a fair amount of time talking about predictions, we’re not really in the prediction business. Rather, our investment team comes up with scenarios and then assesses which of those scenarios seems most likely (which becomes our base case) and which of them seem less likely (and those become alternative scenarios – both good and bad). We then track events over time to look for clues as to which scenario appears to be unfolding. Our base case scenario is that we continue to be in the midst of a growth slowdown. We don’t think we’re headed for a recession in 2019. We recognize that this expansion has been long, that growth is slowing, and that investors are on edge. As the news flow waxes and wanes, we could see more volatility. The recent gains in the stock market may not hold. We very well could retest the Christmas Eve lows, as economic data continues to signal further slowing. Investors should brace for yet more volatility. We don’t think another winter is coming, but it likely won’t be a straight-up recovery either. There are simply too many issues weighing on investors. However, our base case scenario does call for stocks to end the year higher, even if there is further downside volatility in the interim. With the Fed now patient, taking a wait-and-see approach, that’s one fewer issue to worry about. There are plenty of other issues that can still contribute to volatility, such as a protracted government shutdown, more chaos in Washington, Brexit, and other geopolitical risks. The most pressing issue still weighing on investors, which is likely to contribute to volatility in 2019, is the U.S.-China trade war.

Trade war or cold war?

The U.S.-China trade war will be a pivotal event for 2019. Investors are weighing just how long the trade dispute will go on and the significance it will have for the global economy. Are we witnessing a fundamental shift in our relationship from cooperation to competition? Are we merely in a trade war, negotiating over tariffs, intellectual property, and technology transfer, or are we entering a new type of cold war that goes beyond the economic sphere to include ideological conflict and political hostility as we compete for global influence and hegemony? Will we be able to avoid the so-called Thucydides Trap – the idea that historically whenever there’s been a transition from one superpower to another, military conflict is often the result? The short answer is that we think the two countries have, in fact, entered a new era. We don’t expect a shift from cooperation to competition but rather a mix of the two – “coopetition.” We think China and the U.S. will be able to successfully avoid the Thucydides Trap, and we don’t think the two countries have entered a new cold war. But we do think that the U.S. and China will increasingly compete in terms of ideology, values, culture, soft power, and global influence.

Base case scenario: the trade war gets resolved

While the nature of our relationship with China will continue to evolve in fundamentally new ways over the next decade, as China continues to grow in economic power and influence, we think the current trade war will ultimately be resolved this year. It’s in both countries’ interests to resolve it in order to maintain growth in an otherwise slowing global growth environment. We expect further volatility in the near term as the negotiations continue to progress and both parties jockey for advantage. It won’t necessarily be smooth sailing from here. But we think that we will see a resolution shortly, and resolving this dispute will help contribute significantly to a global market recovery. With that said, we are mindful of less likely, though still possible, alternative scenarios. We remain vigilant about the possibility of such scenarios.

Optimistic about 2019

We’re optimistic about 2019. As we mentioned, while we could see more downside volatility, and even retest the Christmas lows, we think ultimately the year will end with positive returns for both the stock market and diversified investors. Rest assured that we’re on guard, watching all the global macro risks carefully. We have positioned our diversified asset allocation strategies with a balance of offensive characteristics (e.g., exposure to stocks, including international and emerging market stocks, and real estate) and defensive characteristics (e.g., cash and short-term Treasury bills, Treasury notes, high-quality investment-grade fixed income, value-oriented stocks, real estate with defensive characteristics, and noncorrelated alternative strategies).

- As we look forward to the rest of 2019, we’ll leave you with some reasons for optimism:

- After a year when the stock market has declined, the following year is almost always positive.

- Bear markets in one year are almost always followed by a positive return the following year.

- The third year of a presidential administration is almost always positive for the stock market.

- It’s rare to have a bear market without a recession, and we don’t see a recession in the near term, thus we expect a recovery from the bear market (and that recovery may already be unfolding).

- The economy is still growing, albeit at a slower pace than previously, but it is growing nonetheless.

- The Fed has taken its foot off the brakes, likely pausing its interest rate hikes.

- The U.S. and China are engaged in negotiations over the trade war and it’s in both countries’ interests to eventually strike an agreement.

While it may still be cold outside, we think the season is about to change. Winter will be passing soon. Prepare for spring. But be prepared, too, in case a cold spell suddenly and unexpectedly blows through again in the meantime. Get ready for the most-anticipated event in two years, when Daenerys Targaryen and Jon Snow arrive in Winterfell. By April, the weather should be nice.

As always, we appreciate your confidence and trust in us. Should you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out to your Wealth Advisor.